Kenya’s Economic Pivot: Mining Licenses and Creative Leases Redefine Resource Wealth

A New Era of Digital Licensing and Formal Investment

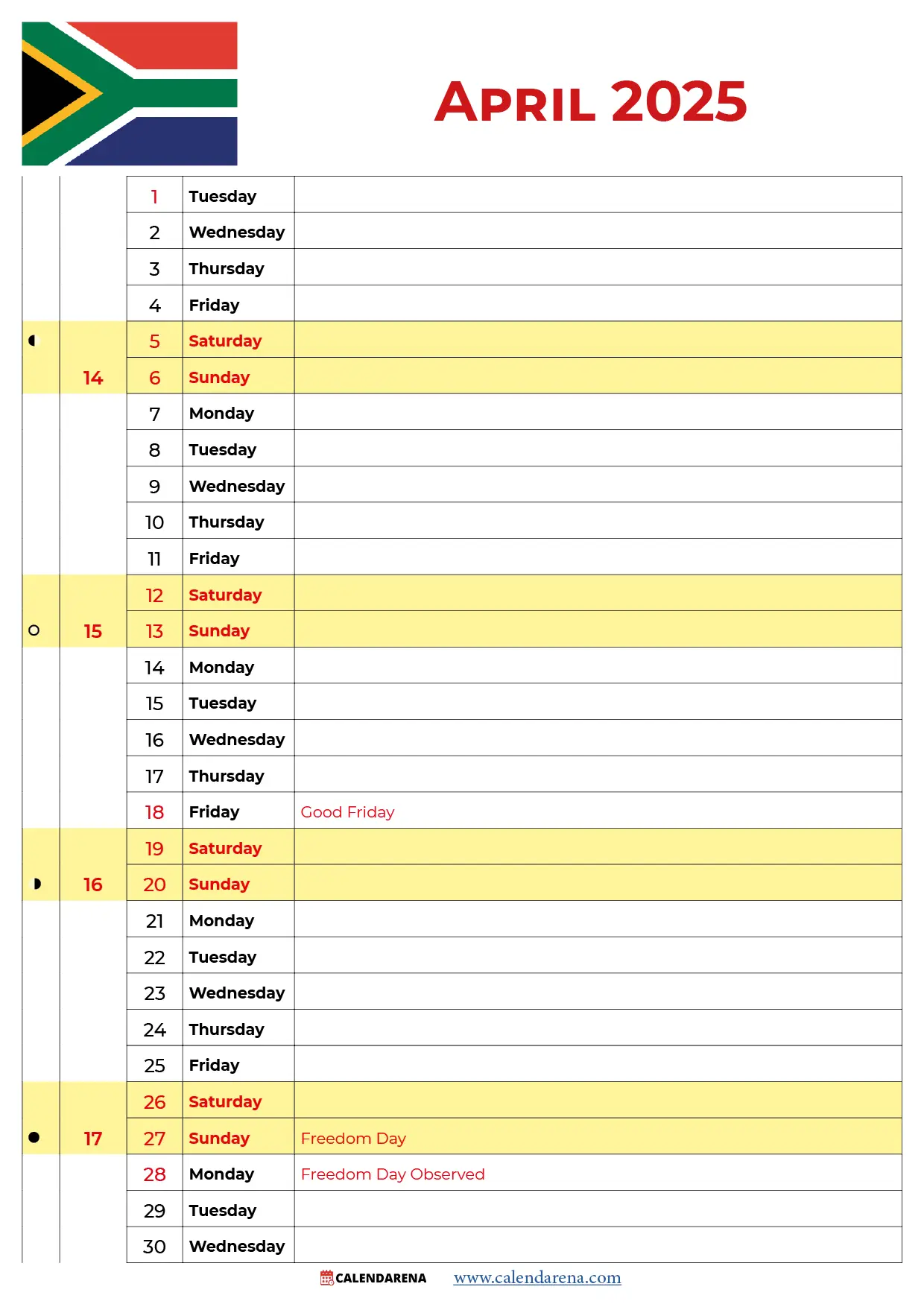

Nairobi is witnessing a significant shift in how it manages its natural wealth, a move that signals a broader economic strategy to attract private capital and formalize the extractive sector. The government’s recent gazette notice, which listed 14 companies to be granted new mining licenses, is more than a procedural update; it represents a calculated effort to unlock value in counties that have long sat on untapped potential. Among the beneficiaries are Roben Aberdare (K) Limited in Nyeri and Tripod Mining Company Limited in Kwale, both of which are set to begin aggregate extraction under a new regulatory framework. This push for formalization is anchored by the digital Mining Cadastre Portal, a platform designed to strip away the opacity of the old paper-based bureaucracy. By moving licensing online, the state is not only speeding up approvals but also inviting public scrutiny and integrating environmental oversight directly into the workflow. For investors, this digital pivot reduces the “hidden tax” of corruption and delay, making Kenya a more predictable destination for capital. However, the implications extend beyond ease of doing business. As Kenya’s economic rise with energy growth gains momentum, the ability to efficiently manage mineral rights will determine whether the country can convert its geological assets into tangible development without triggering the social friction often associated with mining. The transition suggests that the government is finally ready to treat mining not as a peripheral activity, but as a core pillar of its diversification strategy, demanding the same level of transparency and efficiency as its financial services sector.

Revolutionizing Agriculture and Regional Corporate Strategy

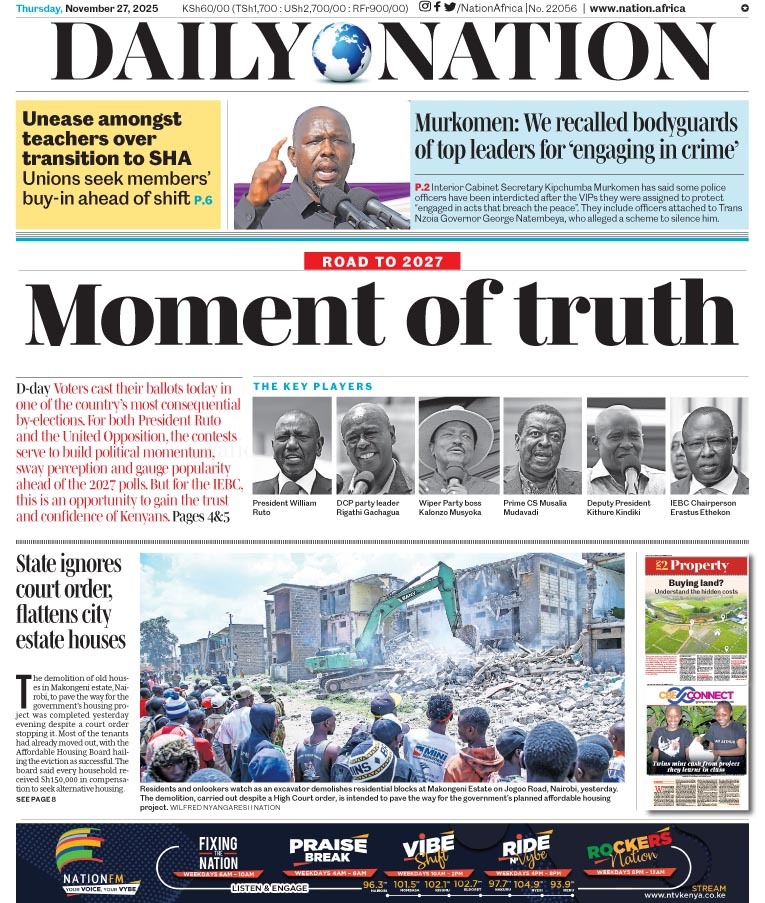

While excavators gear up in the mining counties, a quieter but equally profound revolution is taking place on Kenya’s farms. The traditional model of informal tenancy is rapidly giving way to what experts are calling “creative leases,” a trend that allows landowners to monetize their assets without losing ownership. This shift is crucial for modernizing the sector, as it bridges the gap between land-rich but capital-poor owners and commercial operators who possess the technical expertise to drive yields. We are seeing four primary models gain traction: crop-share agreements, long-term leases, joint ventures, and profit-sharing partnerships. Each of these creative leases reshape agriculture future dynamics by aligning incentives. For instance, a joint venture allows a landowner to retain a stake in the upside of high-value export crops, whereas a long-term lease provides the operator with the security needed to invest in expensive irrigation systems. This evolution in land governance is happening alongside a broader corporate realignment in Southern and East Africa. A prime example is the news that industrial giant Barloworld is set to end its 80-year JSE streak, a move that reflects a growing preference among legacy firms to restructure away from the glare of public markets. This regional context matters because it highlights a shift toward private equity and direct investment vehicles, which are often better suited for the long-term horizons required in both agriculture and mining. Furthermore, technology acts as the connective tissue for these sectors. Artificial intelligence is now driving digital innovation and strategic investment, enabling precision farming that uses satellite imagery to optimize fertilizer use, and machine learning algorithms that reduce the environmental footprint of mineral prospecting.

Balancing Growth with Community Safeguards

Despite the optimism surrounding digital portals and commercial contracts, significant risks remain that could undermine this economic pivot if left unchecked. The primary concern is the potential for exclusion. As farming becomes more capital-intensive and mining more regulated, there is a danger that smallholders and artisanal miners could be pushed to the margins. The rapid deployment of AI and complex legal structures creates an information asymmetry where local communities might sign away rights they do not fully understand. It is critical that the drive for efficiency does not outpace the capacity of local institutions to enforce safeguards. Successful transformation will depend on investment and security trends that prioritize inclusive growth, ensuring that profit-sharing isn’t just a clause in a contract but a reality on the ground. Without robust data governance and clear legal protections, the modernization of these sectors could widen the inequality gap rather than bridge it. Looking ahead, the most likely outcome is a multi-speed economy where highly efficient, tech-enabled commercial projects coexist with smaller, traditional operations. The government’s challenge will be to build bridges between these two worlds, perhaps by using the tax revenues from the formal mining sector to fund capacity building for small-scale farmers. If regulators can maintain this delicate balance, Kenya stands to create a resilient, export-oriented economy that benefits more than just a few well-connected players. The alternative is a return to the cycle of boom, bust, and grievance that both investors and citizens are desperate to avoid.