Africa’s Turning Point, from Startups to Minerals, as Investment Flows Rebound in 2025

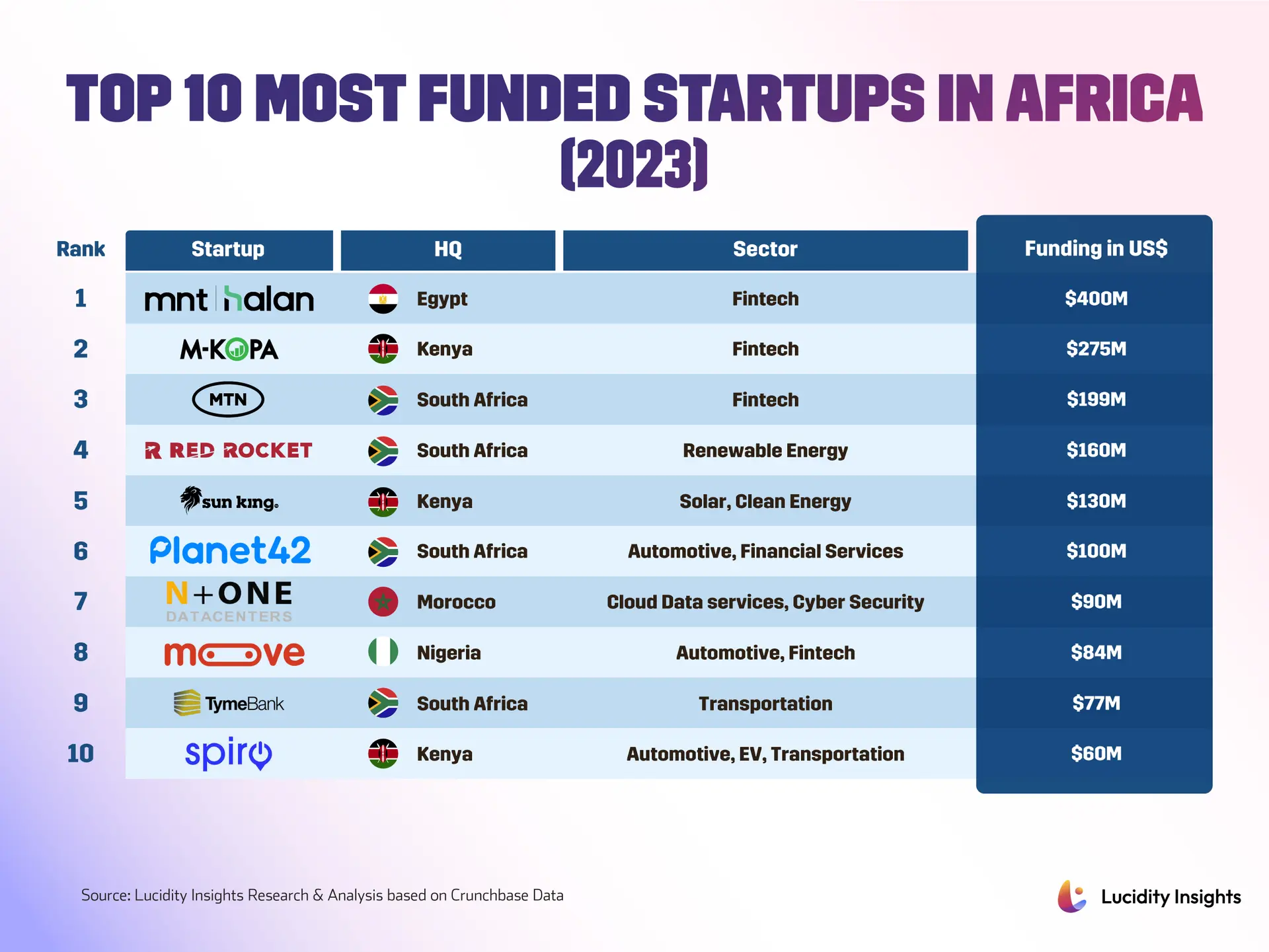

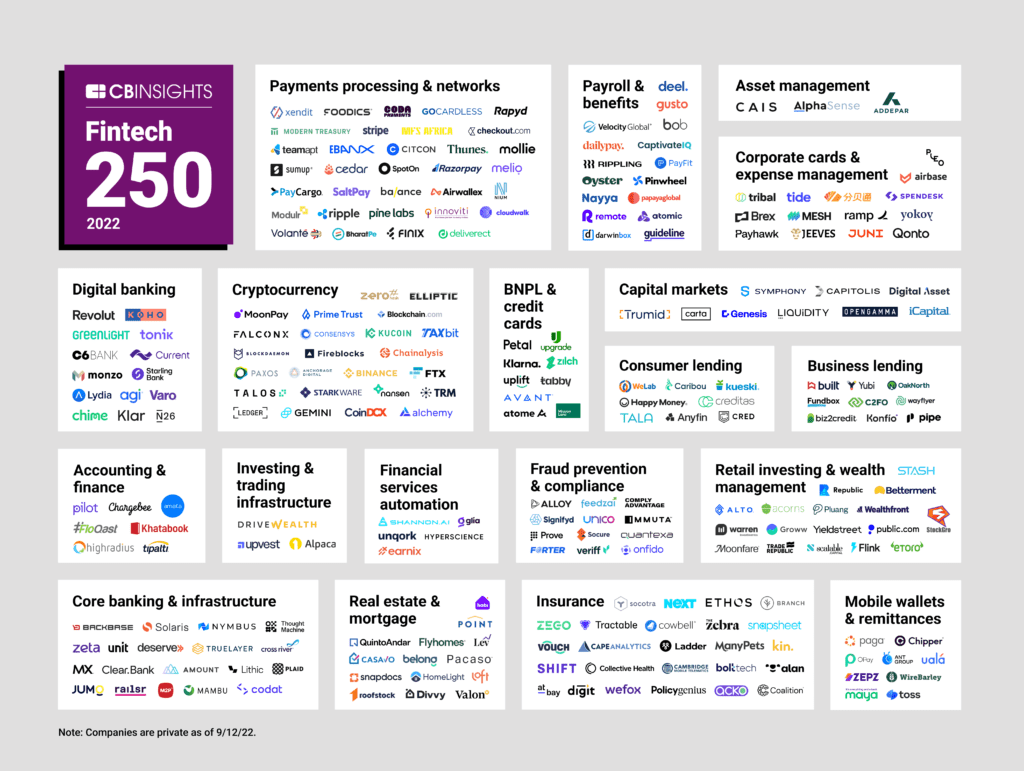

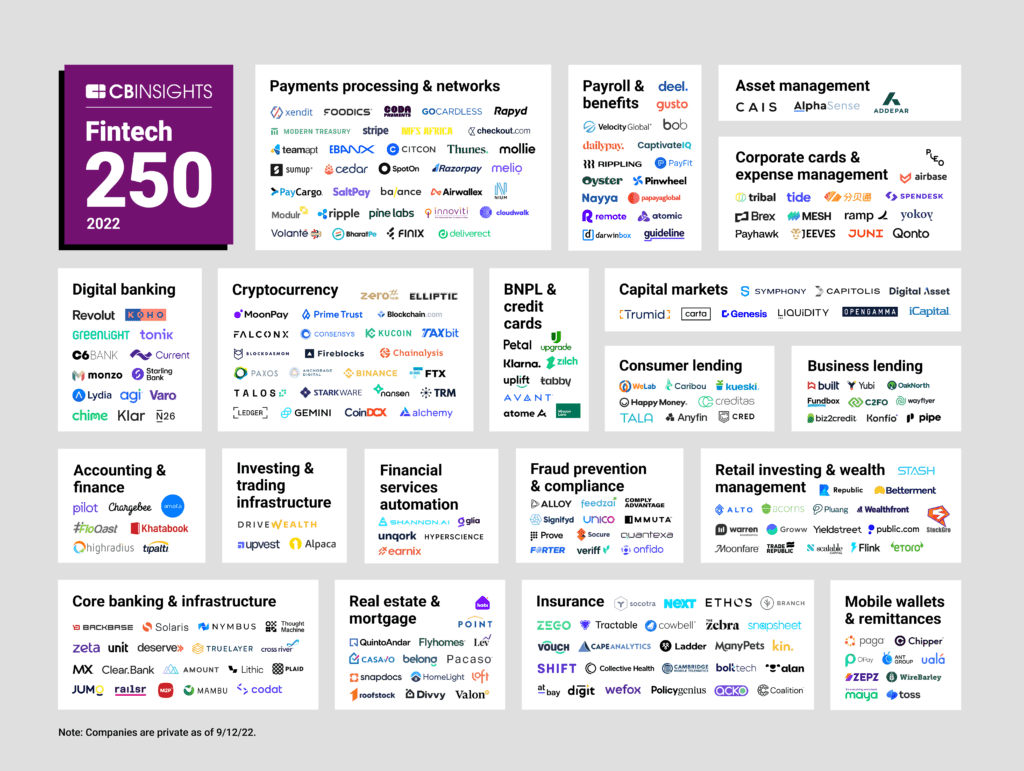

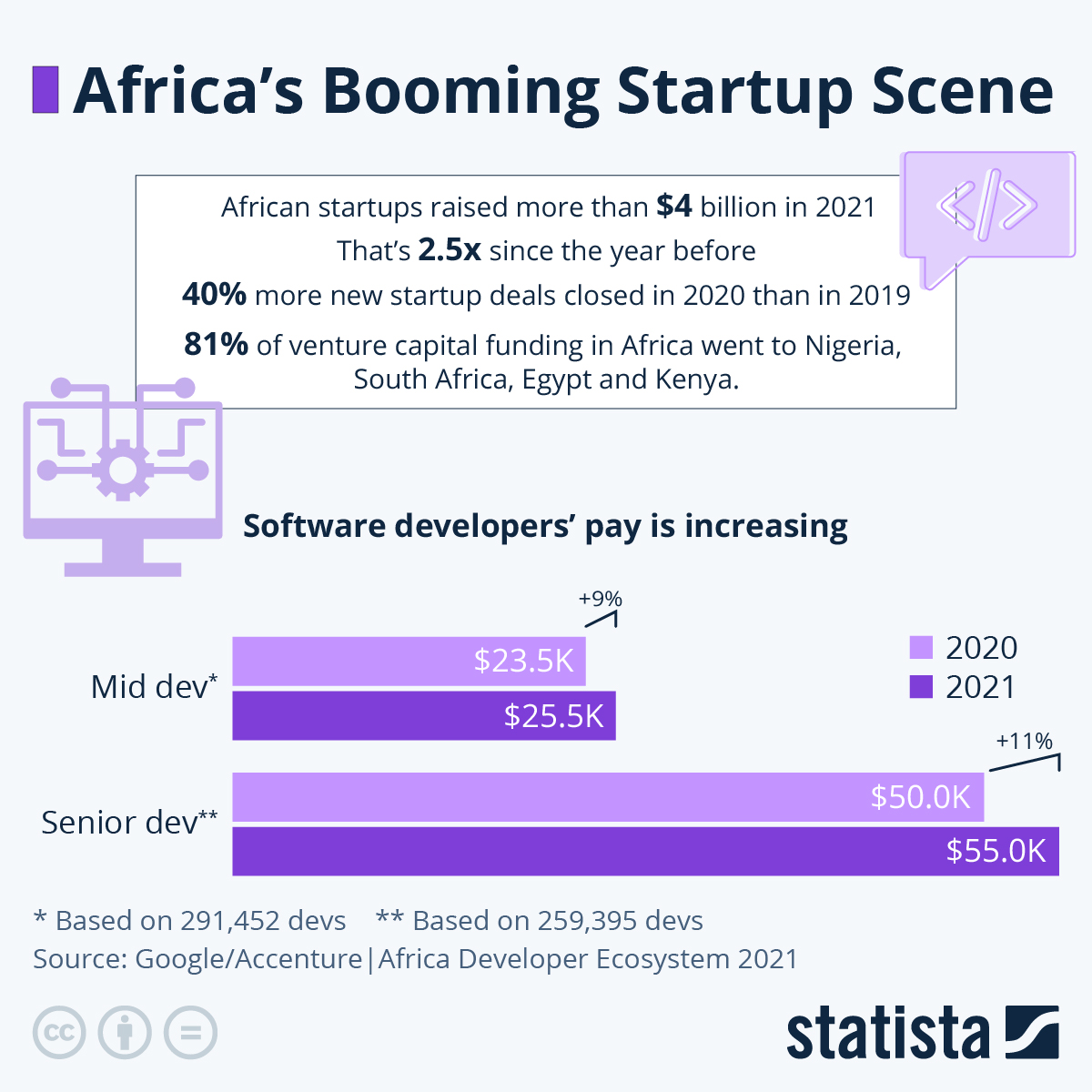

Something’s shifting across Africa’s economic landscape, and 2025 might just be the year we look back on as a genuine turning point. After two tough years that saw venture capital pull back, the continent’s startup scene has come roaring back to life. Data from multiple trackers shows African tech funding climbed about 33 percent year on year, pushing the total past the US$3 billion mark. That’s a milestone that follows steep declines in 2023 and 2024, and it signals renewed investor appetite across sectors from fintech to clean energy and mobility. Large transactions helped move the needle, including Egypt’s property platform Nawy raising $75 million, Senegalese fintech Wave securing $137 million in debt financing, and Spiro’s $100 million round in e-mobility. Clean energy and climate adjacent firms were particularly visible, with Sun King closing a substantial $156 million securitization to scale solar home systems and South Africa’s SolarSaver announcing $60 million in equity. It’s not all unalloyed success stories, though. Some funded companies are recalibrating, like e-commerce player Sabi, which reduced staff by 20 percent despite raising $38 million as it pivots toward traceable exports. This illustrates a broader trend where investors are asking for clearer paths to revenue and discipline on burn. The momentum matters because startup success will increasingly depend on deeper markets, better logistics, and industrial capacity. That’s especially true for Africa’s resource sectors, where a parallel story is unfolding.

From Raw Minerals to Industrial Opportunity

At climate and trade negotiations, African leaders have made a compelling case that mineral wealth should be a tool for climate action and industrialization, not just a one way export lane. Europe has signaled support for African efforts to capture more value from critical minerals, offering technical cooperation and, in some instances, finance to build processing and refining capacity. The logic is straightforward, and also urgent. New carbon related trade rules in some markets, including the European Union’s carbon border mechanisms, can penalize high carbon exports. By adding processing, beneficiation, and cleaner manufacturing locally, African countries seek to both protect export revenues and create jobs. Translating mineral wealth into climate aligned industry requires large capital, risk tolerant partners, and clear regulations. It also intersects with the startup story, since many clean tech and energy firms will be suppliers, customers, and innovation partners for nascent domestic value chains. Beyond venture capital, established market events are creating large cross border flows. The Africa Investment Forum and trade expos recorded billions in commitments and contracts, with one notable industry showcase reporting $48.3 billion in deals alongside more than 112,000 attendees and over 2,000 exhibitors. This reflects how private sector and state backed finance are simultaneously mobilizing toward infrastructure, industrial projects, and value chain development.

The SME Financing Gap and What Comes Next

At the policy level, attention has turned to small and medium enterprises, which make up the majority of African businesses and employ most workers. Development banks and industry experts warn of a chronic financing shortfall, estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars. One practical instrument that could help is factoring, the sale of invoices to a financier to get immediate cash. Experts say scaling factoring volumes to the equivalent of roughly 10 percent of GDP, or about €240 billion for the continent, could unlock working capital for thousands of firms, smoothing the path to growth and formalization. Women entrepreneurs are a central piece of that puzzle. Despite high rates of entrepreneurship among African women, persistent financing gaps remain, with estimates pointing to a near $50 billion shortfall for women led businesses. Evidence presented at recent investment forums shows women tend to have lower default rates, suggesting that tailored financial instruments for female founders could yield both social and economic returns. The convergence of renewed startup funding, big ticket infrastructure and trade deals, and a push to capture more value from mineral resources sets Africa on a more diversified growth trajectory. But the transition isn’t automatic. It will require patient capital, stronger domestic regulatory frameworks, targeted instruments to de risk industrial projects, and practical measures to close the SME financing gap. For investors, the message is that Africa offers compound opportunities, where backing a fintech or a solar firm can create downstream demand for local manufacturing and logistics. For policymakers, the urgent tasks are to create predictable rules for investors, scale invoice financing and other working capital tools, and design incentives that encourage local processing of commodities while meeting climate obligations. If 2025 is a recalibration year, then the coming months will define whether this momentum becomes durable. Will capital continue to flow into scalable, revenue generating startups? Can public and private actors translate mineral wealth into competitive industrial capacity? The answers will shape employment, exports, and a new generation of African businesses that link local markets to global value chains. The story of Africa’s investment rebound is still unfolding, and it promises to be consequential.