Mali and Senegal Assert Resource Control as Africa Navigates Complex Social Realities

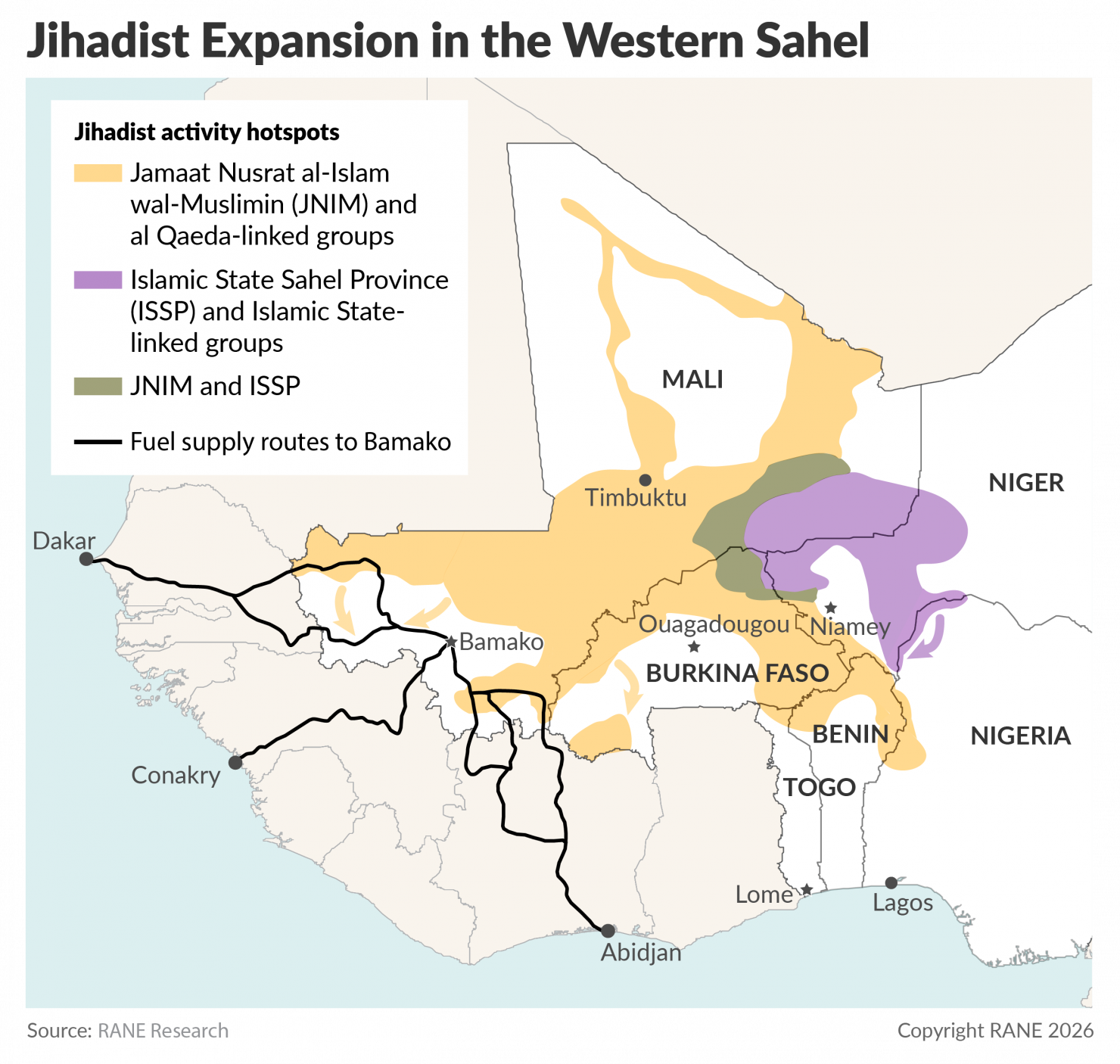

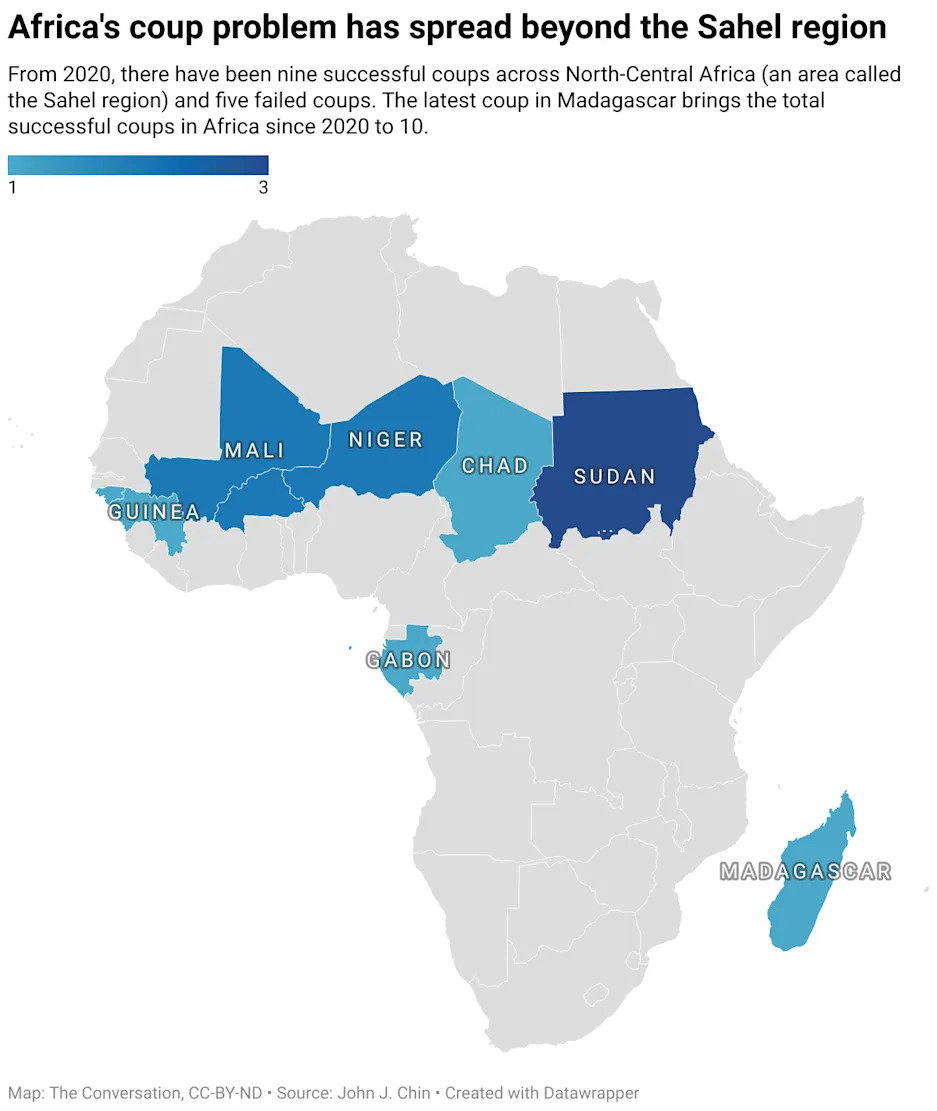

Across a continent rich in natural resources, African nations are increasingly taking charge of their wealth. Recent developments in Mali and Senegal highlight this push for greater resource sovereignty, even as broader challenges like rural inequality and historical social abuses remind us just how complex progress can be. Take Mali, one of Africa’s largest gold producers. They’ve announced plans to create a state-owned holding company to manage their significant mining interests. This isn’t a small move; it’s a direct response to past tensions, including a lengthy dispute with Canadian mining giant Barrick Gold, which saw the military-led government tighten regulations, seize gold stocks, and even temporarily shut down the lucrative Loulo-Gounkoto mine. This strategy, similar to what we’ve seen in Niger and Guinea, aims to ensure Mali’s mineral wealth genuinely benefits its people, addressing vulnerabilities exposed by a model once dominated by foreign firms. Meanwhile, Senegal’s state oil company, Petrosen, is making waves with an ambitious $100-million program to explore new onshore oil fields. While Senegal’s significant entry into oil and gas production is relatively recent, thanks to offshore projects like Greater Tortue Ahmeyim and Sangomar, this new initiative signals a deeper commitment to national control over oil production. It joins countries like Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, and Angola in empowering national oil companies to become front-line explorers and operators. Building local expertise and financial muscle is critical here, don’t you think? It’s about challenging foreign dominance and capturing more value from their own resources, though developing the necessary capacity remains a formidable challenge for Senegal’s energy future.

However, the pursuit of resource control doesn’t automatically translate into equitable benefits for everyone. Research from elsewhere offers a crucial warning: governance reforms, even those meant to empower local communities, can sometimes worsen existing inequalities. A scientific study on Nepal’s forestry decentralization program, for example, showed that dominant ethnic groups, with their higher literacy, capital access, and political ties, were better equipped to navigate bureaucracies and reap the rewards, leaving minority groups behind. This is a vital lesson for African nations considering decentralized resource governance. Reforms simply must be designed to include and benefit marginalized groups; otherwise, they risk entrenching social divides rather than alleviating poverty. It’s a powerful reminder in societies battling historical inequities. Shifting gears to a more optimistic note, advancements in agriculture are playing a complementary role in fostering stability. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is leading efforts to introduce next-generation wheat varieties, resistant to heat and rust diseases. Through participatory trials, farmers in Central India are rapidly adopting these improved seeds, boosting productivity in the face of climate stress. CIMMYT’s work is spreading, with partnerships in places like Nigeria, where new wheat varieties co-developed for local conditions are already being praised by millers. These agricultural innovations, fueled by genomic tools and advanced breeding, are essential for global food security in a changing climate, and they significantly contribute to rural stability and economic diversification, especially for farming communities.

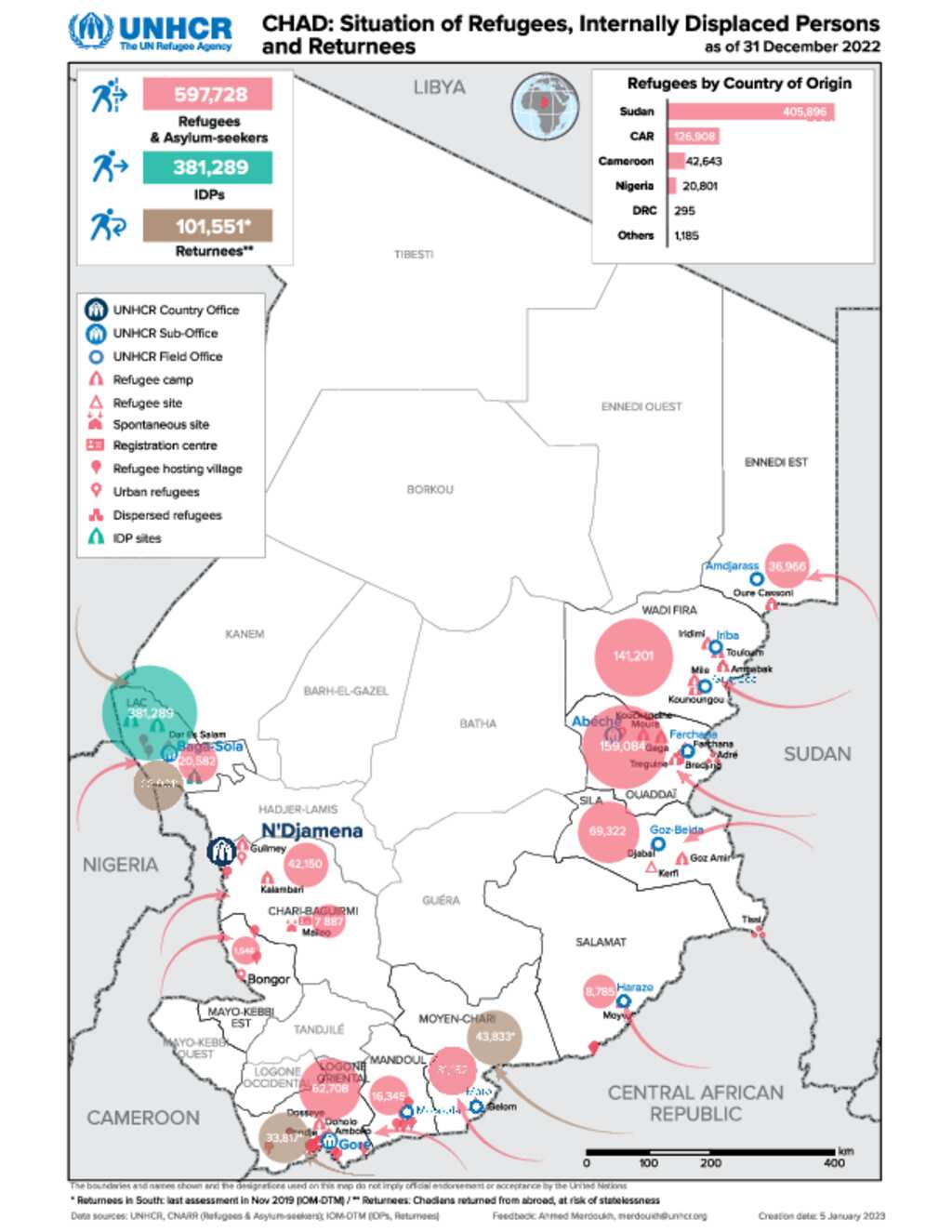

While states forge ahead with economic strategies, the long shadow of historical social trauma also demands attention. A recent case in France, where prosecutors identified a 79-year-old accused of sexually abusing 89 minors over five decades across multiple countries, including Morocco, Algeria, and Niger, underscores the difficult and often global path to justice for victims. Public appeals to find witnesses and victims highlight the immense challenges authorities face in addressing abuses that span borders and time. For African nations, often with their own histories of conflict and trauma, these developments are a stark reminder: economic and governance progress must go hand-in-hand with commitments to justice and healing. As Mali and Senegal work to transform their natural endowments into sustainable prosperity through assertive resource management, the bigger picture reminds us that economic gains are only truly valuable if they’re linked to social equity and justice. The lessons from decentralized forestry governance serve as a caution that reforms without inclusive frameworks can deepen inequalities. Yet, innovations like climate-resilient wheat varieties offer real hope for food security and rural well-being. Balancing these priorities isn’t just important, it’s central to Africa’s 21st-century development. Success won’t just come from discovering and extracting minerals or oil, but from ensuring these gains genuinely address longstanding social divides and contribute to healing historical wounds. With thoughtful policy, stronger institutions, and regional cooperation, don’t you agree the continent can harness its immense natural wealth to build resilient, equitable societies for all? After all, true progress encompasses both economic growth and social justice, leading to a more secure and just future.